A rare week goes by that transgendered (trans) persons are not addressed in the news. Initially the focus was on the famous. With these revelations, trans and questioning youth could begin to see their secret selves modeled in society. With access to the internet youth can educate themselves about gender identities. Such information may provide them language to describe their own authentic experiences that may not be mirrored in their immediate surroundings. In January of 2017 National Geographic’s special issue was entitled Gender Revolution, and showcased multiple aspects of gender across the globe. Clearly, moving away from binary gender assignment is not just an American issue.

I was always aware that trans people existed. But even after four decades working with youth, I was not knowledgeable about transgendered children. Once in consultation group, perhaps 28 years ago, I was asked if a young boy who only played with the “girl toys” in the play room meant that he was gay. I was unwilling to assign such a judgement at the time. Looking back, I think I really misjudged a possibility out of my ignorance. Now I believe that this boy may have been exploring another gender identity, a female one, in the safety of the playroom.

This blog topic—a clinical vignette of one youth’s journey—is for therapists who may not consider themselves “experts” in assisting transgender youth. I ask you to reconsider limitations you may have set for yourself. Transgender youth require competent and professional mental health care, not necessarily the care of an “expert.” We need to be informed. I invite you to use the experiences and capabilities you already possess to support these high-risk clients on their journey to manifest their true selves. I advocate that we as mental health professionals expand our hearts and minds and simply educate ourselves to use the skills we have. I was successful in doing just this. In this and a subsequent posting I share our journey.

In describing all of my work, I only use pseudonyms. Al’s treatment lasted from early adolescence into adulthood and thus the gender pronouns I use in telling Al’s story are those he used, naturally changing over time. There are two parts to this topic so that adequate consideration can be given to the unfolding of Al’s quest for true self-connection. Part two will be posted in several weeks.

Alice, age 13 asked her mom to call for an appointment. I’d seen her at age seven for five months, diagnosing and treating her for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) after the death of her father from a long illness. At that time, Alice’s mother, a young widow, described Alice as being “just like her dad, a creative and intense child.”

Now, her mother reported that her daughter was “questioning” her gender identity and her original symptoms of anxiety were increasing. Returning to therapy with me, Alice reported a tendency to be self-deprecating, and feelings of deep shame. She had occasional thoughts of suicide. She described having poor boundaries with peers, such as “taking care of”—at her own emotional expense—peers who might be depressed, suicidal, or cutting. Alice described herself as an “anxious overthinker” who felt a discontent that she didn’t fully understand.

Alice’s mom reported that her daughter thought she may be gay, and that she had recently begun to use the term transgender. Mom felt confused and did not know how to help Alice. I replied that this specific area was not my expertise. The family lobbied to be seen anyway, as their way of starting to explore gender issues. Alice’s previous treatment had been beneficial, and she felt comfortable working with me. In the initial joint session, we agreed that they could move to a more seasoned therapist on this topic should I be unable to be helpful. By this time I’d read the March/April 2016 Psychotherapy Networker-“The Mystery of Gender, Are Therapists in the Dark?” with interest, but no intention of treating a person with gender questions. I then began to devour anything I could get on this topic and immediately enrolled in a CEU course on gender issues that I had previously bypassed.

Once Alice was seen alone, she clearly described why she felt she was transgendered, not gay. Since her father’s death Alice and her mom had grown even closer than before, a connection that Alice did not want to jeopardize. She told her mom that she was gay as a way to ease into a discussion on gender, expressing concern about how hard her mom might take her news. Initially, Alice avoided discussing gender issues with her mom because they “always ended up in a tense debate” which undermined their closeness. Alice hung on to her female pronouns with her mom for an extended period to give her mom time to adjust. This deeply ingrained pattern of protecting her mom remained a theme throughout treatment. With her friends and me, Alice soon requested we use male pronouns. She felt the needed to explore her newly identified feelings and her options with someone outside her family.

Alice stated that she was not gender fluid nor questioning. She had been educating herself on the internet, and now had the words to describe some of her internal experiences. She expressed deep discontent with her body and how she looked. Her outside (body) and inside sense-of-self were at odds. “I’m like a Jenga tower well into the game. I have an unstable foundation. I want to have a solid self.” Alice’s mom let her wear sports bras to decrease emphasis on her developing breasts. Alice cut her hair and changed her look to appear more androgynous. According to Elijah Nealy’s model of transgender emergence, Alice had passed through the stages of Awareness and Information Seeking. She was advancing through Disclosure to Significant Others when beginning treatment with me. Disclosure itself is a lifelong task for trans people. Unfortunately, I did not have the benefit of Nealy’s book, Trans Kids and Teens until it published more than 3 years into Alice’s care.

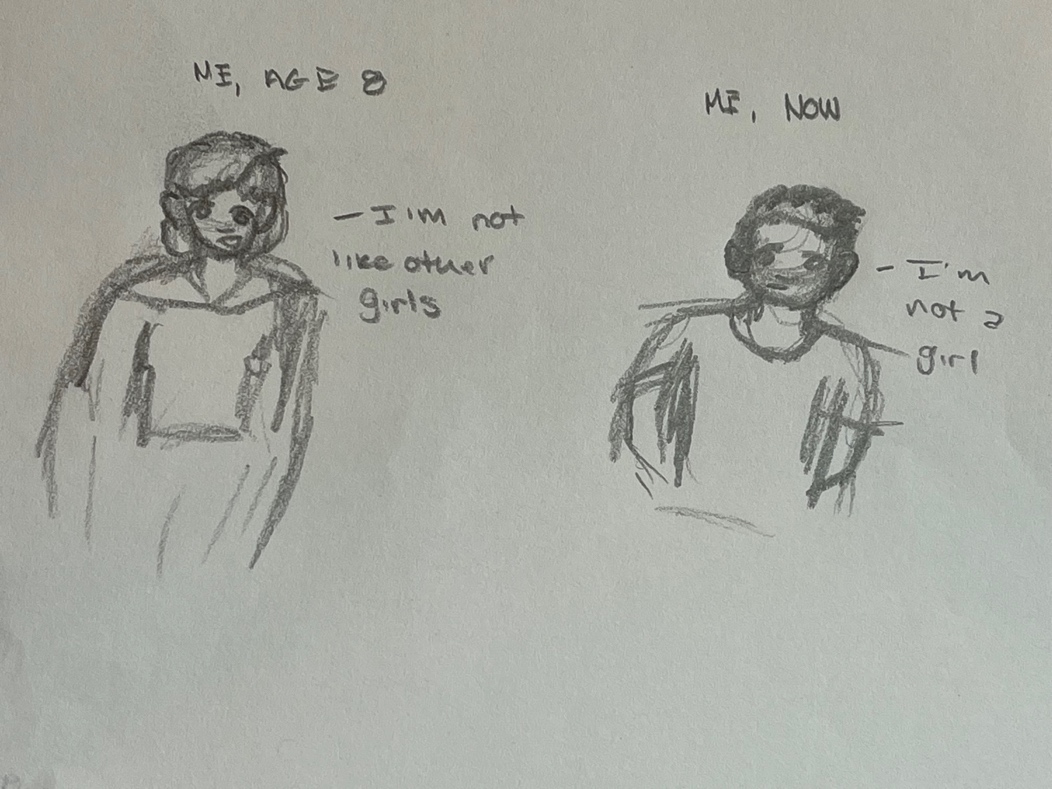

As sessions progressed, Alice shared some clear markers of the Gender Dysphoria in Adolescents (GD) diagnoses. She began to describe images and feelings from younger years of desiring to be a boy when being a tomboy wasn’t satisfying enough. While her girlfriends were being princesses, Alice’s images were of being the prince down on one knee asking for their hand in marriage. These images and feelings were disconcerting for her until a few months prior when she learned about transgender people, just a few months prior to our first session together. Not all of the GD criteria could be met at the time I assigned an initial diagnosis, so I included it as a tentative one. Soon Alice changed her name to Al, and eventually Al changed pronouns to he/him in the community.

Early in our sessions Al expressed deep frustration that his body was wholly disconnected from his deep sense-of-self. In the sand tray pictured above he started with the white dove in a cage striving to get out. “The bird is me—the cage is my body.” This cage is surrounded by anger (red dress “evil doll”), depression (black outfitted “evil doll”), and the “evil bunny girl” (Figures 3 & 4). In a subsequent sand world, this bunny was revealed as “gender dysphoria.” Al described the colors of the flowers as correlating to those on the trans flag.

Although therapy focused on a strong gender narrative, Al’s pervasive anxiety prevailed. His trans issues would get caught in the circular negative/disparaging thinking patterns which augmented his self-deprecating statements and actions. Well into treatment, his anxiety system would hijack even normal life experiences, expanding Al into a full panic. That said, it is important to bear in mind that during the course of our treatment, COVID-19 occurred. Over and above normal adolescent issues of school pressures, peer relationships, and balancing demands and self-care, Al also experienced close family deaths of people and pets, active shooter drills and lockdowns at school, and anxieties about how his treatment would proceed.

Al used the Sandtray process freely prior to and after the need for COVID precautions. When COVID necessitated telehealth, I utilized expressive arts methods including Al’s own artwork and poetry, along with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) in an attachment framework. Al felt that sharing his original art and poetry in this blog would be too revealing, so here I am emphasizing the Sandtray aspect of his therapy. Initial disclosure of his male person brought Al support among his peers and teachers. Challenges were more difficult with family. Initially he struggled to be his “Alice self” when visiting relatives out of state. After coming out to them, he received a birthday card “To my Granddaughter,” and was told, “you’re such a pretty girl, it’s a shame to waste it.” These events fueled his anger, frustration, and despair.

Part of Al’s emerging trans identity expressed itself in a rejection of society’s binary thinking and its pressures to “be a girl and do girl things.” One example of this can be seen in the above sand world (Figures 5 & 6). Al set strong and supportive items in the center. As he placed the pride flag, he emphatically said “Yes!” Note that he also placed the “evil bunny girl” of dysphoria in the center cluster. Each corner depicts his view of how society thrust femaleness upon him, even from birth. He called the corner with the household items, “the good Christian housewife corner.” He shared the social/familial message that “This is who you should be, this is the life of a girl.” He then stated, “This has nothing to do with me!” At the end of this session, Al pushed over the bunny, face down in the sand. He addressed the tension between his internal truth and the external expectations of others in many sessions.

Understandably, Al’s mom struggled with losing her dreams of a life with her future daughter. I referred to her own treatment early in Al’s therapy. When the full diagnosis of GD was reached for Al, she could not believe it to be true. Like many parents, she reacted with, “It’s a phase…. You are too young to know…. You’ve tried a lot of hats (interests/activities), this is just one more.” Eventually she began to support Al, but two-and-a-half years into treatment admitted that “just to be able to function” she was still in deep denial about Al’s trans status. At one point she was under attack by distant relatives who asserted that parents who support gender transition were child abusers. In the conflictual political climate surrounding trans persons, it is easy to see why a trans youth might feel, as Al sometimes did, that “I’m bad, the world would be better off without me.” As transgender advocate Cecelia Chung asserts, perhaps it is society that is suffering from Gender Perception Dysphoria. Sharing this journey with Al, I’ve come to believe that it is not so much gender identity itself that causes distress, but society’s reactions that create and augment anguish.

In Nealy’s framework, the fourth stage of transition is Exploration about Identity and Self-Labeling. The fifth is Exploration of Transition Issues which includes options for body modification. As with most “stages” these are not strictly linear. For Al these two areas were entwined and were where much of the therapeutic work was done over a period of years. To do justice to this young man’s story, I will be sharing more of the aspects of his journey in the second and final installment.